Nothing To Live Up To

Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL 2008

Nothing to Live Up To was a solo exhibition dedicated to recent paintings by Howard Fonda. The selection of paintings on view concentrated on the interdependent relationships between nature, existence and time, examining the perpetual wonder, hope and heartache that is inherent to all life.

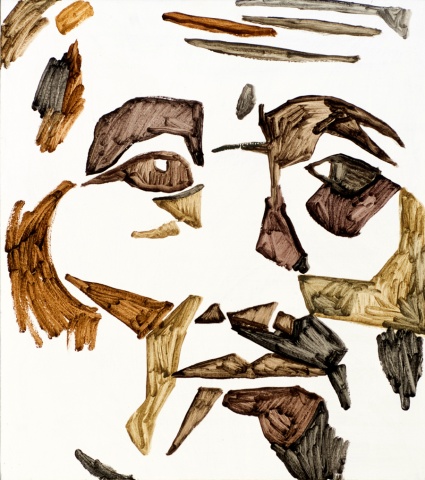

Nothing to Live Up To holds suspect our overly commercial, superficial and constructed "world", and boldly aims beyond toward truth. Fonda has developed a large body of work over the past several years that delves into transcendental thought with a vibrant palette and complex perspective. Using a direct process called alla prima, oil paint is applied wet into wet to the canvas in one sitting. This directness offers a tension and immediacy similar to the process of drawing. For Fonda, the formal qualities of painting - the emphasis on color, line, shape and texture - are equally as important as the conceptual elements being interpreted on the canvas.

Howard Fonda talked with Allison Peters, the Director of Exhibitions at the Hyde Park Art Center, about his paintings and drawings. Here are some excerpts from that conversation.

(Alison Peters) Immediately when a viewer enters the gallery, it is clear that the works are hung in an untraditional manner: there are visual pauses created by uneven spacing between canvases, some canvases are markedly closer to each other, and all of the works are hung slightly lower than the “standard” height. The works have been hung somewhat chronologically, beginning with paintings from 2005 at the South end of the space and ending with the most recent work toward the North. As you and I discussed before hanging the show, you had a particular installation design in mind. Explain what influenced your decisions, both architecturally and conceptually when putting together this particular arrangement of canvases.

(Howard Fonda) The long rectangular space (the hallway) originally seemed tough to negotiate. I wasn’t certain how to approach it other than directly. I’m not one for mock-ups or a lot of planning. I prefer to direct my energies to the studio and individual works. If I can arrive at a “successful” painting, I trust it will be strong enough to work in any space or situation. As I began to lay out the work, it became clear that a loose chronology would prove both straightforward and honest, and provide rich context and a challenging view. As my work tends to be singular and specific, rather than serial or aesthetic, a natural narrative made the most sense. I ended up with an immersive installation that allowed for autonomy and (open) narrative.

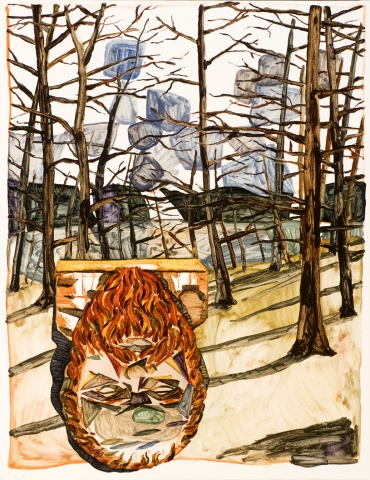

(AP) The way you discuss the exhibition installation draws a connection to the way you also talk about the way space is manipulated in the picture plane. Using color, shape, and form, you like to push and pull the painting and allow for a flattness. The “tree” paintings are a great example of the way space gets mangled, inverted and compounded upon itself. What do you want the viewer to get from this tension?

(HF) I really like contradictions and being able to have my cake and eat it too. A formal push and pull is definitely a core interest of mine. I’ve been trying to imply depth and flatness, or abstraction and representation, in the same painting. Just as I’ve been trying to address both form and content... they’re really the same aren’t they? The form leads to the content or the content leads to the form... the paintings make these demands on the viewer. I’m not certain how this directly relates to the installation, but there is an overlap with the tension, awkwardness and challenges presented. I think this challenge underscores my intent with the paintings... they can’t be taken for granted or be labeled passive. I want them to be tough... aesthetically and conceptually. The Hanging doesn’t have a synchopated pace. There is no constant pitch. I love that. The viewer is forced to find and make meaning of that. And there is meaning to be found!

(AP) Another key aspect of your paintings is that you make them all in one sitting while the entire canvas is still wet, a technique called alla prima, which essentially allows for one layer of paint without underpaintings. The result is incandescent colors, decisively visible brush strokes and any mistake is either incorporated into the composition, or the painting is trashed. Looking closely, not many of the paintings even have sketches beneath them to guide the immediate application of color and forms. What is your interest in this approach to painting?

(HF) I really stumbled (I’d like to think evolved) onto this way of working. It most closely relates to the ideas and sentiments I am trying to understand and express. In many ways, I’m not much of a painter. I came to it rather late and have so much yet to learn. Much of my aesthetic and technical ability is rooted in drawing. I really like the tension this provides. Always moving forward, never back, nothing to “cover” or erase. All is laid bare to decipher. It allows mistakes to sit next to successes. This is integral to my tastes in painting and view of painting as a metaphysical practice, not a mere act of design. Contemporary painting MUST fail in some measure in order to “succeed”, in order to have meaning, in order to hint at truth. I work on one painting at a time - one specific idea, dialogue or narrative. As I mentioned before, this method of painting allows for a directness that parallels my thought process. The work is honest, raw, and close to the bone. It is a conscious move away from the calculated, constructed and (lately) over-polled world one typically inhabits. I’m a romantic (maybe even a Romantic). I buy into the notion of the hermetic and mystical studio practice that transcends time and space. Call me what you will, but I’m sincere. In fact, since we’re on the subject of sincerety, fuck irony, fuck cynicism, and fuck escapism.

This conversation of process and practice naturally leads to (and overlaps with) the specific formal and conceptual decisions in the work. I think it’s pretty obvious the work is highly intentional. Here is where I run out of words and look to the work to pose and answer questions.

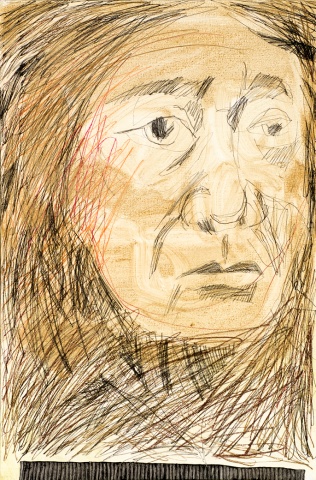

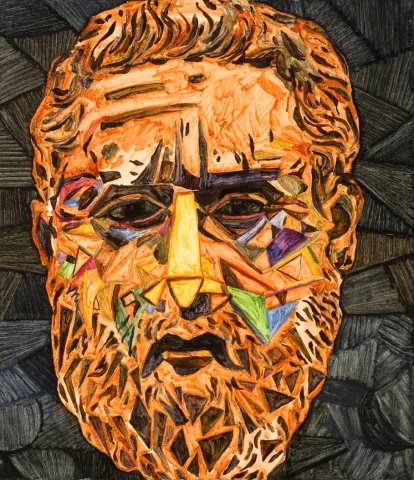

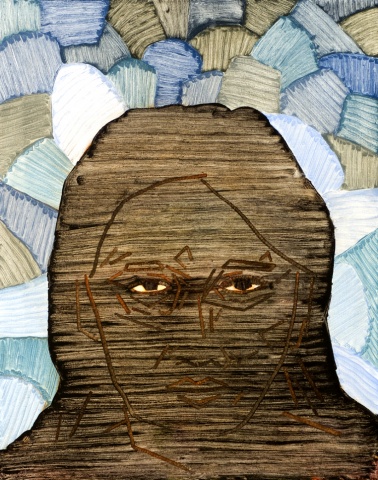

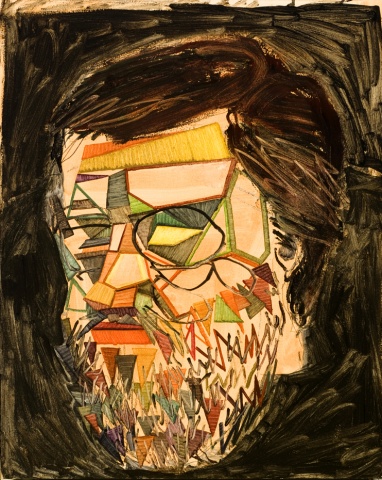

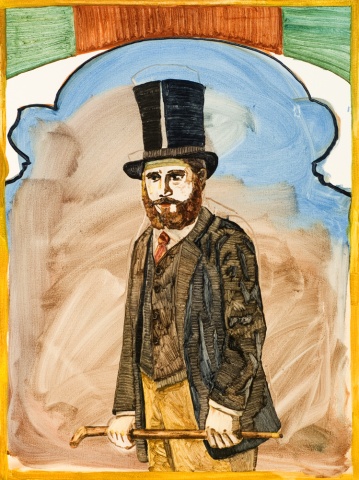

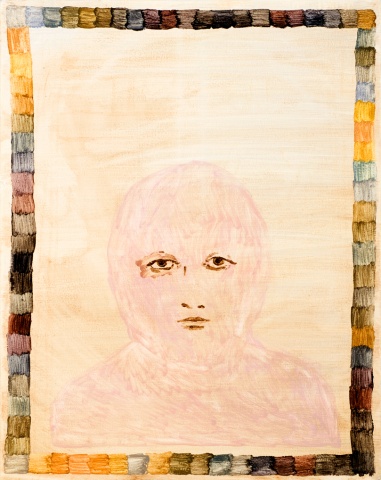

(AP) The portraits in the exhibition include iconic figures such as Pocahontas, Manet, Plato, Socrates, your girlfriend. Some of these individuals are repeated on other pieces. Why, or how, did you pick these iconic figures to be represented?

(HF) Ahh, the portraits. It’s difficult to generalize, but I suppose they are everything and nothing. They represent ideas, influences and adoration just as often as they are a form to hang my aesthetic ideas, influences and adorations. I don’t think it’s necessary to know who is depicted in the paintings – it may augment your understanding or provide an interesting anecdote, but not always provide some answer. I do my best to weave form and content, so no one piece can be boiled down to “this” or “that”, or in this case, “they”. The portraits are more about ideas and ideologies than about legacy or likeness.

(AP) Unlike painters who paint strictly from memory, you are painting from a source image, whether it be a 19th century etching, a Helenic sculpture, a manipulated photograph or from real-life. How does that variation in the generation of the image translate in the way the subject is represented in the painting?

(HF) I do my best to paint from life and often create a still-life or cut out construction. Whether involving photographs or my reflection in a mirror, they are all representations to some degree. Meaning is to be sought and found in these gaps and spaces between… in the ever changing context of things. Color, line, and mark adapt to these changes. One of my aims is to manifest meaning and truth via my experiences with these ever changing forms/ideas. It is a very ontological approach (as pretentious as that sounds).

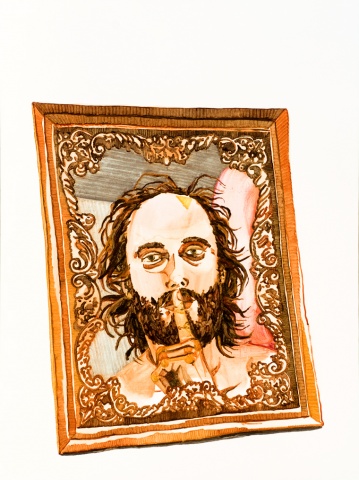

(AP) Images that contain your likeness you seldom refer to as self-portraits. Is this strictly a practical solution to not having anyone else to sit as a model or is there a psychological aspect at play?

(HF) I tend to make a lot of appearances in my work. The reasons are many, but boil down to a couple things. I’m not good at making things up in my head. I have a very solitary studio practice and am typically the only one around to solve a particular formal issue. And, painting is a wonderful place to confront one’s psyche and self-awareness. This is probably the heart and soul of my practice. Here, I find an uneven balance between self-understanding and insecurity. It’s an enlightening rollercoaster that lends meaning to existence.

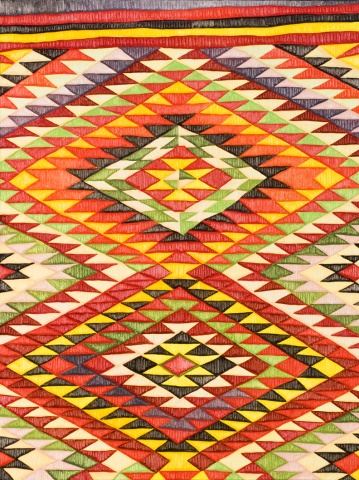

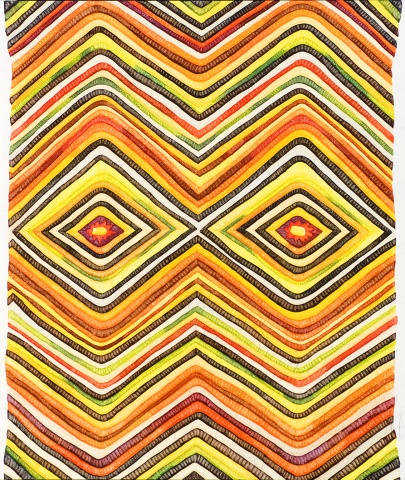

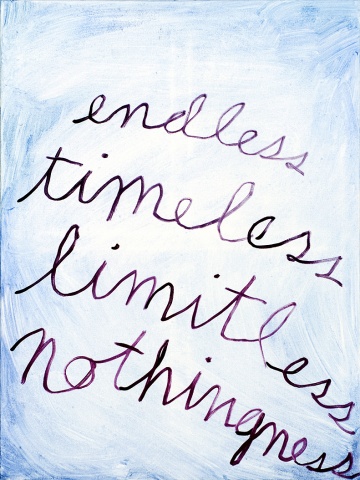

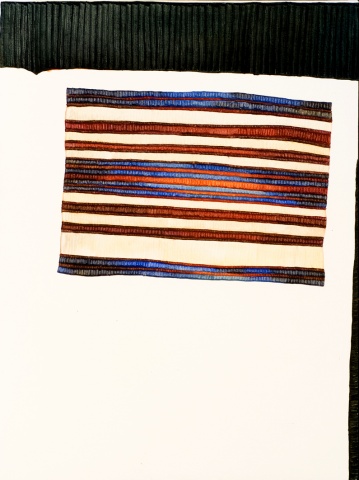

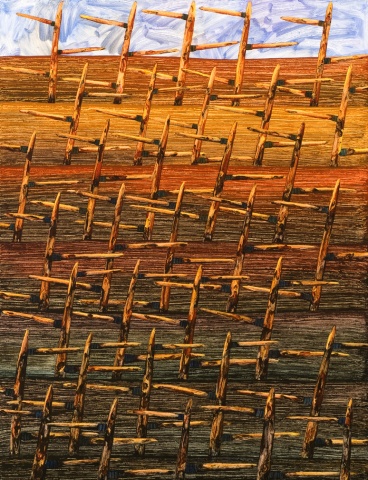

(AP) Many of these works seem to have a particular code or language involved. Several you’ve discussed as your reinterpretation of an ancient text, like the Kama Sutra, or a passage from Plato’s Republic. Other canvases contain words that are strung together alluding to some greater meaning. Additionally, the “pattern” paintings reference Native American textiles, known for intertwining tribal history into garment and blanket designs. How do you see language in your paintings?

(HF) Language plays a big role in my process... formally as much as conceptually. I’m attracted to its directness as well as its ambiguity and nuance. A common theme in my work, it is both abstract and representational. It can hint at meaning or be purely aesthetic This interest broadens to include cultural artifacts, historical dialogue and variants of visual culture. It’s all “language”, right? It’s all a way of finding meaning and truth. It’s all a way of finding guidance… finding someone, something to live up to in this crazy world.